One of my major tasks this year is to do a thorough renovation of my home's energy efficiency - the first completed project is an installation of Solar Photovoltaic Panels. The PV inverter reports the panels' power output to a central server, but I wanted to get hold of this data myself in order to display a chart as part of my OpenHAB panel.

TL;DR

The source and installation instructions for the service are available from Github at planetmarshall/solis-service

I have the service running on a Raspberry Pi under supervisor.

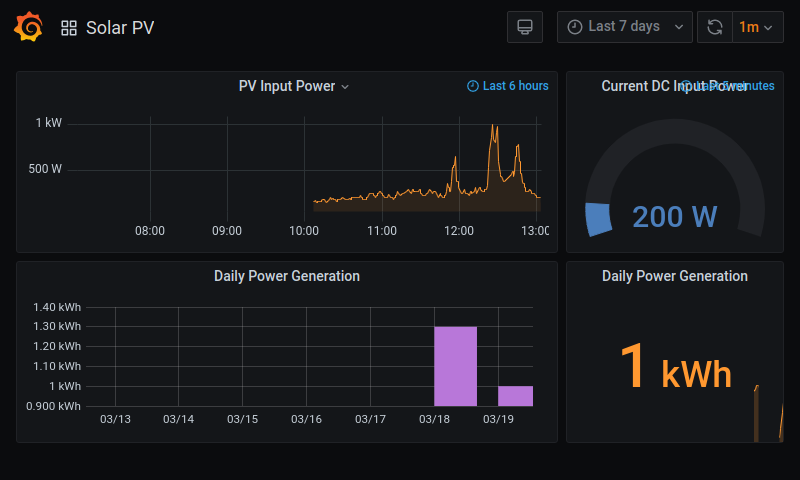

Here's the data displayed in a Grafana dashboard on my Raspberry Pi Touchscreen

Previous work

For previous work along these lines, which I've referred to when creating this solution, see

- graham0's ginlong-wifi

- Darren Poulson's ginlong-mqtt

Unfortunately the protocol has been updated since these solutions were created and

neither of them worked for me. The following applies to firmware version MW_08_512_0501_1.82

Determining the protocol

Redirect the inverter output to a local system

The Web UI for the Inverter offers the option to redirect its output to a secondary server, Server B. Unfortunately,

this option appears to not work with the latest firmware. Instead it's possible to change the Default server entirely,

from the remote Ginlong monitoring server, to a system on the local network. This option is hidden and can be found by

referring to the following page - Ginlong Support

At this point it's useful to have Wireshark open to check that the inverter is actually sending data. We can start examining the data with the following short Python script.

async def handle_inverter(reader, writer):

data = await reader.read(256)

print(data)

async def main():

server = await asyncio.start_server(

handle_inverter,

'192.168.10.9',

9042)

asyncio.run(main())

The initial data from the inverter is a 99-byte message, some of which is immediately identifiable as the firmware version and the local IP of the inverter.

b'...\x00\x00\x05<x...MW_08_512_0501_1.82...\x00\x00...192.168.10.8...\xa8\x15'

However, we know from previous work and from the data available on the ginlong server, that the invert uploads information on energy output and temperature that is clearly not part of this message. It seems likely that this is a "heartbeat", and is waiting for some kind of response before sending the actual data we're interested in.

The "machine in the middle" attack

This isn't quite as nefarious than it sounds, but simply involves intercepting transmissions to and from the inverter so that we can find out what the server response to the heartbeat message looks like. Hopefully it's going to be something simple that we can mimic, and get the inverter to send us the data instead without involving ginlong's server at all

async def read_and_log_response(reader):

data = await reader.read(256)

print(data) # in practice we log more info

return data

async def log_and_forward_response(reader, writer):

data = await read_and_log_response(reader)

writer.write(data)

await writer.drain()

async def handle_inverter_message(inverter_reader, inverter_writer):

server_reader, server_writer = await asyncio.open_connection('47.88.8.200', 10000)

await log_and_forward_response(inverter_reader, server_writer)

await log_and_forward_response(server_reader, inverter_writer)

server_writer.close()

inverter_writer.close()

async def main():

server = await asyncio.start_server(

handle_inverter_message,

'192.168.10.9',

9042)

asyncio.run(main())

As hoped, as soon as we forward on the heartbeat to ther server, we get a response. In turn, the inverter starts sending back a 246 byte message that looks much more interesting.

The server response

In response to the heartbeat, the server sends back a 23 byte message that looks like this -

b'\xa5\n\x00\x10\x11K\x01\xc2\xe8\xd7\xf0\x02\x01\x8f~K`\x00\x00\x00\x00\xa3\x15'

Unless the developers have used some sort of standard serialization format like MessagePack (they haven't - I tried), then trying to figure out the content of the response is a laborious process. Fortunately the message is quite short, and over the course of the day only a few parts of the message change. One portion in particular stands out.

If we assume that the message contains 32bit integers

(in little-endian format), bytes 13-17 represent the

number 1615560335. Work with binary data enough, and some things start to look familiar. This

just happens to be the number of seconds since Thursday 1 January, 1970 - better known as

Unix time.

If we plot the last-byte-but-one, it looks like random noise. This is a good indication that it's a Checksum. This is important because it's likely that the Inverter will verify that the checksum is correct on any message it receives. Fortunately the checksum algorithm is fairly simple, and a bit of trial and error reveals that it's a variation on the ISO 115 Longitudinal redundancy check

from functools import reduce

def checksum(data):

return reduce(lambda lrc, x: (lrc + x) & 255, data)

Decoding the inverter data packet

We could sift through the 246 byte inverter data packet in a similar fashion looking for interesting values, however that would be a tedious process and there's a much better way. Since we've forwarded the data on to the Ginlong server, we can log into the portal and export the data collected for the day. That gives us an indication of what the packet should contain. We can then write a brute-force algorithm that compares the expected data to various decoded values in the data packet and look for correlations.

Here are some results from running the correlation algorithm.

| column | correlation | field | format |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC Current T/W/C(A) | 0.98 | 60 | <I |

| AC Output Total Power (Active)(W) | 0.99 | 116 | <I |

| DC Voltage PV1(V) | 0.98 | 48 | <I |

| Inverter Temperature(C) | 0.996 | 45 | <I |

| Power Grid Total Apparent Power(VA) | 0.99 | 142 | <I |

| Total DC Input Power(W) | 0.99 | 116 | <I |

Note that some of these interpretations are mutually exclusive, for instance AC Voltage and AC Output Freq can't be both 32 bit integers in fields 66 and 67 as they would overlap. In addition some values will correlate due simply to physics, but it's enough of a guide to start extracting information from the packet.

Here's the results of the investigation. Some fields are yet to be determined as I don't have enough data as yet. I've annotated the fields with the appropriate physical unit using pint

return {

"inverter_serial_number": message[32:48].decode("ascii").rstrip(),

"inverter_temperature": 0.1 * unpack_from("<H", message, 48)[0] * ureg.centigrade,

"dc_voltage_pv1": 0.1 * unpack_from("<H", message, 50)[0] * ureg.volt, # could also be 52

"dc_current": 0.1 * unpack_from("<H", message, 54)[0] * ureg.amperes,

"ac_current_t_w_c": 0.1 * unpack_from("<H", message, 62)[0] * ureg.amperes,

"ac_voltage_t_w_c": 0.1 * unpack_from("<H", message, 68)[0] * ureg.volt,

"ac_output_frequency": 0.01 * unpack_from("<H", message, 70)[0] * ureg.hertz,

"daily_active_generation": 0.01 * unpack_from("<H", message, 76)[0] * ureg.kilowatt_hour,

"total_dc_input_power": float(unpack_from("<I", message, 116)[0]) * ureg.watts,

"total_active_generation": float(unpack_from("<I", message, 120)[0]) * ureg.kilowatt_hour, # or 130

"generation_yesterday": 0.1 * unpack_from("<H", message, 128)[0] * ureg.kilowatt_hour,

"power_grid_total_apparent_power": float(unpack_from("<I", message, 142)[0]) * ureg.volt_ampere,

}

Persisting the data

With the protocol determined, we can remove the Ginlong server from the equation and deserialize and persist the data ourselves. I use Influxdb and Grafana.